Prevenção em Odontologia para os agravos da COVID-19

A aplicação de métodos, materiais e correlatos para a correta higiene bucal, essencial para prevenir agravantes relacionados ao novo vírus

Vinicius Pedrazzi

Millena Mangueira Rocha

Fellipe Augusto Tocchini de Figueiredo

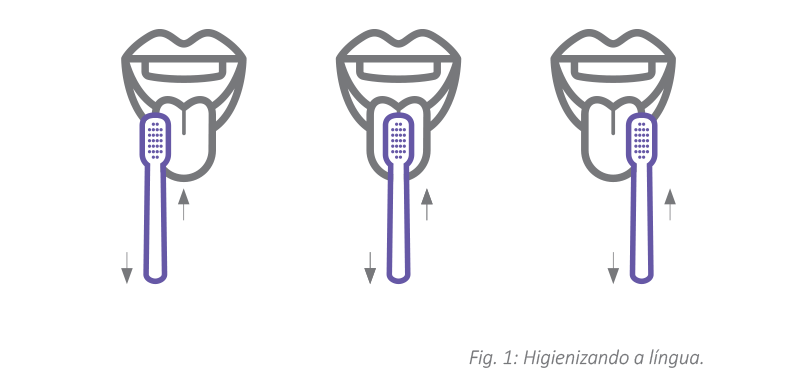

- Higienizar o dorso da língua. Com higienizador específico ou mesmo escova de cerdas macias, tracionar o dispositivo a partir do “V” lingual (papilas valadas) para o ápice da língua, em três ações de “varredura”: 1/3 esquerdo; 1/3 central e 1/3 lado direito da língua (Figura 1).

Importante: a fim de evitar náusea (gag reflex) durante a higienização da língua, apreender a ponta (ápice) da língua com uma gaze limpa e tracionar a língua para fora da boca. Não haverá náusea.

Fazer uso correto e rotineiro do fio dental e/ou de escovas interdentais quando indicadas para portadores de próteses parciais fixas dento ou implantossuportadas (antes da escovação com dentifrício).

Realizar a escovação dental com escova de cerdas macias e brancas (para visualizar se ocorre sangramento – sinal clínico de doença periodontal) e em conjunto com um dentifrício contendo flúor ou outros agentes terapêuticos (exceto o triclosan) – lembrar que um dos diversos componentes dos dentifrícios é o agente surfactante (detergente, que atua na capa de gordura que envolve o material genético do SARS-CoV-2, removendo-a).

Usar enxaguantes bucais (antissépticos bucais), se necessário, com agentes como o cloreto de cetilpiridínio (CPC – quaternário de amônio). Importante: os enxaguantes bucais não substituem a remoção mecânica dos biofilmes (ecossistemas) bucais.

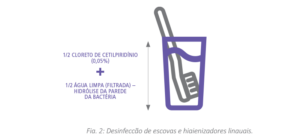

Adicionalmente, cuidar de nossas escovas dentais e dos nossos higienizadores de língua, mantendo-os imersos em solução desinfetante — em um copo descartável ou em um pote de plástico ou louça; indicamos o cloreto de cetilpiridínio diluído em 50% de água limpa para maior eficácia — em quantidade suficiente para cobrir a cabeça e o pescoço da escova e a ponta ativa do higienizador de língua. Trocar o líquido uma vez por semana para evitar a reinfecção após cada uso.

Importante: esse procedimento não é para o uso coletivo de escovas dentais e higienizadores de língua — são instrumentos de uso individual.21-24 (Figura 2)

Para além de todos os cuidados que órgãos como a Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS) e a Anvisa nos têm orientado,torna-se ainda mais premente a orientação e a difusão do conhecimvento sobre a corretae efetiva higiene bucal

Para além de todos os cuidados que órgãos como a Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS) e a Anvisa nos têm orientado,torna-se ainda mais premente a orientação e a difusão do conhecimvento sobre a corretae efetiva higiene bucal

REFERÊNCIAS

1. Smith ML, Gandolfi S, Coshall PM, Rahman PKSM. Biosurfactants: a Covid-19 perspective. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1341. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01341.

2. Graziano UM, Graziano KU, Pinto FMG, Bruna CQM, Souza RQ, Lascala CA. Effectiveness of disinfection with alcohol 70% (w/v) of contaminated surfaces not previously cleaned. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2013 [acesso em 2020 Jul 03];21(2):618-23. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692013000200020.

3. Lammers MJW, Lea J, Westerberg BD. Guidance for otolaryngology health care workers performing aerosol generating medical procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J of Otolaryngol – Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):36.

4. Pedrazzi V. A odontologia e seu papel fundamental na prevenção da disseminação e agravos da epidemia do coronavírus [Internet]. São Paulo: Faculdade de Odontologia de Ribeirão Preto [acesso em 2020 Jul 03]. Disponível em: https://www.forp.usp.br/?p=6296.

5. Magleby R, Westblade LF, Trzebucki A, Simon MS, Rajan M, Park J, Goyal P, Safford MM, Satlin MJ. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 viral load on risk of intubation and mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 30]. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa851. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa851.

6. Scannapieco FA, Rethman MP. The relationship between periodontal diseases and respiratory diseases. Dent Today. 2003;22(8):79–83.

7. Scannapieco FA. Systemic effects of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(3):533-50. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.002.

8. Adachi M, Ishihara K, Abe S, Okuda K. Professional oral health care by dental hygienists reduced respiratory infections in elderly persons requiring nursing care. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5(2):69-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2007.00233.x.

9. de Oliveira LCBS, Carneiro PPM, Fischer RG, Tinoco EMB. A presença de patógenos respiratórios no biofilme bucal de pacientes com pneumonia nosocomial.

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2007;19(4):428-33.

10. Kinane D, Bouchard P, Group E of European Workshop on Periodontology. Periodontal Diseases and Health: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):333-7.

11. Sjögren P, Nilsson E, Forsell M, Johansson O, Hoogstraate J. A systematic review of the preventive effect of oral hygiene on pneumonia and respiratory tract infection in elderly people in hospitals and nursing homes: effect estimates and methodological quality of randomized controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2124-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01926.x.

12. Sona CS, Zack JE, Schallom ME, McSweeney M, McMullen K, Thomas J, et al. The impact of a simple, low-cost oral care protocol on ventilator-associated pneumonia rates in a surgical intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24(1):54-62.

13. Sharma N, Shamsuddin H. Association between respiratory disease in hospitalized patients and periodontal disease: a cross-sectional study. J Periodontol. 2011;82(8):1155-60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100582.

14. Santos PSS, Mariano M, Kallas MS, Vilela MCN. Impact of tongue biofilm removal on mechanically ventilated patients. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2013;25(1):44-8.

15. Santi SS, Santos RB. A prevalência da pneumonia nosocomial e sua relação com a doença periodontal: revisão de literatura. RFO UPF [Internet]. 2016 [acesso em 2020 Jul 02];21(2):260-6. Disponível em: http://revodonto.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S1413-40122016000200019&script=sci_arttext.

16. Zhou P, Liu Z, Chen Y, Xiao Y, Huang X, Fan XG, et al. Bacterial and fungal infections in COVID-19 patients: a matter of concern. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020; 22:1-2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.156.

17. Zheng Z, Chen R, Li Y, et al. The clinical characteristics of secondary infection of lower respiratory in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chin J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;2:270–4.

18. Pedrazzi V, Sato S, de Mattos MGC, Lara EHG, Panzeri H. Tongue-cleaning methods: a comparative clinical trial employing a toothbrush and a tongue scraper. J Periodontol. 2004;75(7):1009-12. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.7.1009.

19. Fedorowicz Z, Aljufairi H, Nasser M, Outhouse TL, Pedrazzi V. Mouthrinses for the treatment of halitosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD006701.

20. Oliveira-Neto JM, Sato S, Pedrazzi V. How to deal with morning bad breath: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17(6):757-61.

21. Sato S, Ito IY, Lara EHG, Panzeri H, Albuquerque Jr RF, Pedrazzi V. Bacterial survival rate on toothbrushes and their decontamination with antimicrobial solutions.

J Appl Oral Sci. 2004;12(2):99-103.

22. do Nascimento C, Sorgini MB, Pita MS, Fernandes FHCN, Calefi PL, Watanabe E, Pedrazzi V. Effectiveness of three antimicrobial mouthrinses on the disinfection of toothbrushes stored in closed containers: a randomized clinical investigation by DNA Checkerboard and Culture. Gerodontology. 2014 Sep;31(3):227-36. Epub 2013 Jan 15. doi: doi: 10.1111/ger.12035.

23. do Nascimento C, Trinca NN, Pita MS, Pedrazzi V. Genomic identification and quantification of microbial species adhering to toothbrush bristles after disinfection: a cross-over study. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60(7):1039-47.

24. do Nascimento C, Paulo DF, Pita MS, Pedrazzi V. Microbial diversity of the supra- and subgingival biofilm of healthy individuals after brushing with chlorhexidine – or silver-coated toothbrush bristles. Can J Microbiol. 2015;61(2):112-23.